For three months every year, the Himalayan north is in the grip of a quiet war against the freezing cold. It’s the kind of chill that makes diesel heaters less a convenience and more a necessity. The irony is cruel: up there, on the roof of the world, the summer sun is generous, pouring its gold over barren peaks. But once it leaves, it leaves nothing behind.But what if the mountains could hold onto their summer warmth instead? What if the heat of June can be bottled and uncorked in Jan? A team of scientists from IIT Bombay and National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, thinks it’s possible. And the trick, they say, lies in a salt. Strontium bromide, a chalky white salt, when heated, releases water and stores that energy as chemical bonds. When cold returns, and moisture is reintroduced, the salt rehydrates, releasing heat. They call it a thermochemical reactor.The IIT Bombay team wants to use this principle to create seasonal ‘heat banks’ for Himalayan homes — simple, safe, and sustainable. Like an ember tucked under ash, strontium bromide would hold onto the balmy feeling of summer, waiting patiently through the long Himalayan cold, before discharging it again. In the lab, this transformation worked perfectly across six full cycles — summer to winter and back again. The team says it can go through hundreds more.The idea was born of a personal experience. Rudrodip Majumdar, an associate professor (energy, environment and climate change programme) at National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, remembers standing on the snowdusted trail to Tungnath, a biting wind on his back.“The stars were beautiful,” he recalls. “But people here walked miles to gather firewood. Diesel was all they had. And the generator made a lot of smoke and noise.” That night stayed with him.

So, he and his colleagues designed a module small enough to stand beside an LPG cylinder, strong enough to warm a Himalayan home for four bone-chilling months. It is a self-contained unit: a solar collector, a reactor chamber filled with strontium bromide, an air circulation system, and sturdy insulation lined with glass wool. No smoke, no sound, no moving parts, no mess.It works on endothermic (heat absorbing) and exothermic (heat releasing) reactions. When hot air is sent into the reactor, the salt changes to a monohydrate form by releasing water and absorbs heat. When moisture is reintroduced, it reconverts to the hexahydrate form by releasing heat. The absorption and release of heat happens through making and breaking of hydrogen bonds of the salt crystals. The studies on reactor configuration and performance have been published in the peer-reviewed scientific journals ‘Applied Thermal Engineering’ and ‘Renewable Energy’.The reactor performance can be controlled through geometrical configurations, choice of thermochemical material (reactive salts), as well as flow arrangements. “You can get these modules in Gujarat or Rajasthan and ship them to the hills,” says Sandip Kumar Saha, mechanical engineering professor at IIT-B, who led the study, which had postdoctoral fellow Kalpana Singh and PhD scholar Ankush Shankar Pujari as part of the team. Chandramouli Subramaniam, a chemistry professor and a member of the IIT-B team, says the Indian Army has shown interest in the module. The team has partnered with a startup enterprise to carry out field trials at altitudes of 13,000ft for the Army.The economics too makes sense. Diesel-based heating in remote areas can cost up to ₹78 per kWh when environmental penalties are factored in. The salt-based system costs as little as ₹31 per kWh in Leh. Challenges remain. The system is yet to be tested in homes. Summer sunlight and winter humidity vary across the Himalayas. Initial costs are high. But Majumdar insists the dream is worth chasing. “Energy poverty should not exist in the 21st century. The remotest parts of the country should be made energy secure” he says.He hopes the system will ensure no child has to study by diesel fumes, and no woman has to walk miles in the snow for firewood. He is true to his salt.

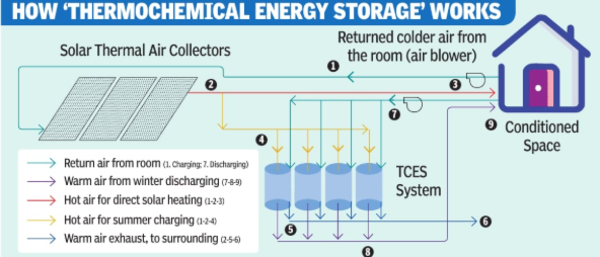

The reactive salt (strontium bromide hexahydrate) is stored in a steel case called the ‘open thermochemical reactor’

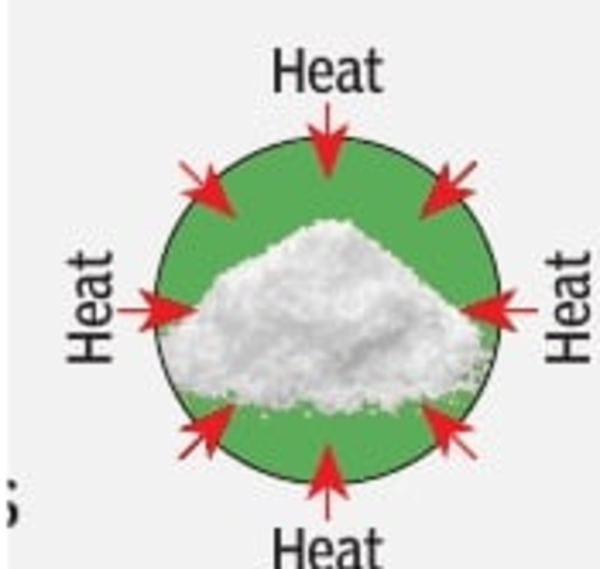

CHARGING | When hot air is sent into the reactor, each molecule of strontium bromide hexahydrate releases five water molecules and turns into strontium bromide monohydrate which absorbs the heat. This dehydration process is endothermic.

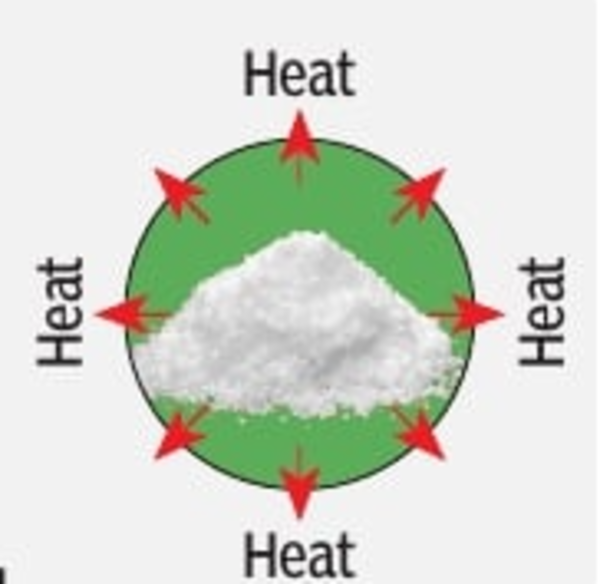

DISCHARGING | When moist air at ambient temperature is sent into the charged reactor, the monohydrate salt absorbs the moisture and returns to its hexahydrate form, releasing heat. This rehydration process is exothermic.

The released heat is carried by the air flowing through the reactor to heat the surroundings